Cruising sailors are embracing competition, thanks to faster boats, better tech, and events that blend racing with adventure.

Ocean-crossing rallies showcase competitive cruising, none more spectacular than the ARC’s start from the Canaries to St. Lucia. Courtesy World Cruising Club

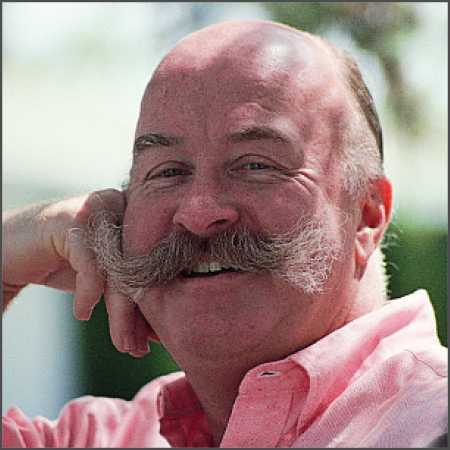

The late, great Larry Pardey—who, as a sailor, was ahead of his time in so many ways—was the most competitive cruiser I’ve ever met. Like many cruising sailors (myself included), Pardey was influenced as a young man by round-the-buoys and nearshore racing, long before he set off for distant horizons. And through the many books and articles that he co-authored with his wife, Lin, it was quite clear that he undertook the pursuit of offshore voyaging in a calculated, efficient manner. To Larry, solid seamanship was the art of sailing safely, but also quickly and efficiently, with optimal sail trim and razor-sharp maneuvers at all times. The attention to detail ensured fast passages, which were always the ideal ones. As the Pardeys’ editor and a reader, I knew all this well before I was commissioned to write a biography of them, called As Long As It’s Fun. But in the course of my research for the book, on the waters off New Zealand, it took a few outings of actually sailing with Larry before I really got the point.

The day it was truly driven home was on an event for classic yachts called the Mahurangi Regatta. We were in the Bay of Islands aboard the Pardeys’ wooden 34-foot gaff-rigged cutter, Thelma, built in 1895. I was assigned to the mainsheet, all 130 feet of it, with nary a mainsail winch in sight. I thought I’d handled the assignment fairly well right up until the race was over, with a final jibe to the anchorage. At that point, I was fairly bushed, and in retrospect, my effort was indeed sloppy and half-hearted. Which is when Larry let me have it.

I’ve long since forgotten the exact words, but I recall the gist perfectly: If you call yourself a sailor, you stay on top of all things, at all times. It’s not only the right thing to do, it’s the respectful one. If you can’t be bothered to sail well, and effectively, go find something else to do.

After making modifications to his 40-footer, Soulmates, the former race boat was ready for open-ocean sailing and knocked off 17 knots under a double-reefed main in the Gulf Stream. Adam Loory

Yes, the race was finished, but the captain—the competitor—was still in charge. That was the last jibe I’ve ever really blown. Lesson learned.

Which brings me to the larger subject of competitive cruising, which I believe is a term that lends itself to modern times. Performance cruisers and speedy cruising catamarans—both of which power the contemporary sailing market—are lighter, stronger, faster and more technologically advanced, as are the sails that drive them. Connectivity is now all-oceans, which makes for better offshore forecasts and more-accurate routing. And more and more events are following the rally formula: not races, per se, but bringing like-minded sailors together in appealing venues that are social and, yes, competitive.

Don’t just take my word for it. Let’s meet some of the folks on the cutting edge of this sea change.

The Sailor

Adam Loory was an impressionable young yachting journalist (also like me) when we first crossed paths covering the America’s Cup in Australia in 1987. He found a far more interesting way home, joining seasoned cruising and racing sailors Jim and Diana Jessie for a voyage that took them first to Cyprus, and later across the Atlantic. The Jessies had commissioned their custom 48-foot Bill Lapworth design, Nalu IV, to race in the Transpac before embarking on their circumnavigation. It made for some lasting memories.

Adam Loory retired from his longtime job at UK Sailmakers to go cruising with his wife, Jenni. Courtesy Maureen Koeppel

“I learned that sailing around the world is doable for mere mortals. You didn’t have to be [Joshua] Slocum or Robin Lee Graham,” Loory says. “You’ve got to pay attention and learn a lot of stuff, but it can be done. And on Nalu, we pulled off lots of 200-mile days. So, I also learned you could make tracks and didn’t need to spend all your time in the middle of the ocean.”

The Jessies were performance-oriented sailors with a quick, rangy boat that enabled their offshore goals and ambitions. Many moons later, Loory chose a similar course.

After a lengthy career as general manager at UK Sailmakers International, Loory retired to go cruising with his wife, Jenni. Over the years, he’d seriously campaigned a couple of racing boats on Long Island Sound, starting with an Express 37 before moving on to a custom Rodger Martin-designed 40-footer previously owned by renowned boatbuilder Eric Goetz. As a potential cruising boat, Soulmates hearkened back to his days on Nalu: “I knew I needed at least 40 feet of waterline and a boat that could knock off those 200-mile runs.”

That said, Soulmates needed some modifications to go cruising. The water-ballast tanks had long been removed, with their space converted for stowage (you don’t need 2,000 pounds of ballast when racing with 10 crew on the rail). Forward, a new windlass was installed, as well as a sprit for the ground tackle, to keep the anchors from banging on the plumb bow. Astern, a new Watt and Sea hydrogenerator provides 10 amps when sailing at 6 knots and 20 amps at 8 knots. A new lithium battery bank was also included in the refit.

A stint in the yard at Scarano Boat in upstate New York provided creature comforts, with the bonus of considerable weight savings. The structural work included raised cockpit coamings and a crash bulkhead in the forward ring frame. For the interior, wood accents gave the staterooms a homey feel, though the furniture itself was built of fiberglass with cored panels; even the teak-and-holly floorboards have a foam core.

Competitive cruising boats come in all shapes and sizes. Ron Boehm’s Antrim 52, Little Wing, has been a fixture in cruising-class events in the Caribbean for many years. Matthew Burzon

As not only a retired sailmaker but also a retired racer, Loory calls Soulmates “a terrific compromise,” one that hit 17 knots reaching across the Gulf Stream under a double-reefed main off the coast of Florida. An original plan for a circumnavigation has been scaled back, and this summer, Soulmates will head Down East to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then north, perhaps as far as Newfoundland. Appropriately enough, his boat speaks to his soul. In the dozen years he’d owned the boat before setting out cruising, he’d sailed it only in flat, protected waters. The ocean sailing has been a revelation: “It’s just a dream to sail in waves.”

The Broker

As I learned with Larry Pardey, you get to know a lot about people when you go to sea with them, and that was again the case in 2018 when I boarded the custom 57-foot Sky for the Regata del Sol al Sol from Tampa Bay to Isla Mujeres, Mexico. I met Josh McLean, a former US Air Force navigator who was serving in the same capacity for our 450-nautical-mile passage. Almost immediately, I knew I was in the company of a kindred sailing spirit.

Prior to joining the Air Force, McLean was a boat-crazed kid who grew up sailing on the Great Lakes. As his military service was winding down, he thought that a second career in the marine industry might be a fine option, and even dabbled a bit in brokering small powerboats while still on active duty. But it wasn’t until he was out of the Air Force and had relocated to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, that he got his big break. That’s when and where he met yacht broker and naval architect David Walters, who not only sold boats, but he also built his own designs—the Cambria line of performance cruisers.

“I learned that sailing around the world is doable for mere mortals. You didn’t have to be [Joshua] Slocum or Robin Lee Graham. You’ve got to pay attention and learn a lot of stuff, but it can be done.”

Walters took McLean under his wing. Later, when Walters died, McLean took over his brokerage business, David Walters Yachts, where he remains the head honcho. “It was really great to learn under his mentorship,” McLean says. “With his eye for good designs, and his ability to put pencil to paper and really knock it out of the park with boats that looked great and sailed well, he set an example of what a yacht broker could be.”

Along with selling used boats, McLean’s company currently reps two brands with serious sailing chops: the bluewater Hylas line and the Italian-built cruiser-racers Grand Soleil. But he remains a close observer of the entire sailing market, and has strong opinions about its current state. “As modern manufacturing has evolved, and you look at some of the materials options like carbon and the different synthetics you see not only in hulls and decks, but also in the sails, the technology and design aspects have evolved, and yachts have naturally become more performance-oriented,” he says.

The market for performance-cruising monohulls like the sleek Grand Soleil 52 LC has never been stronger. Courtesy Grand Soleil Yachts

“A lot of manufacturers,” he continues, “including Hylas, Hallberg-Rassy, Oyster and Swan—which traditionally have been in that bluewater space—have started pivoting into performance designs. People like to sail fast. Even when cruising, they like to get where they’re going. And even classic production builders like Beneteau and Jeanneau, you’re seeing broader transoms, taller rigs, more sail area…. They’re edging in the same direction.”

When I asked McLean to summarize his typical client, if there is such a thing, his answer surprised me: “More and more people come to us with an idea of what they want to experience with the boat, not necessarily with a specific brand or model in mind. A lot of the time, we’re in touch with people a couple of years in advance of their purchase, as their dream kind of evolves.” And, once again, some level of competition is often part of the package.

“There are more ‘commuter’ cruisers out there, who may not have months at a time to go sailing,” he says. “So, the destination becomes more important. And you see more races, like Annapolis to Newport, that cater to cruising classes. And the boats are more dual-purpose. You do the race with your pals, and once that’s over, you put the cushions back on and enjoy the cruising lifestyle on a New England cruise with your family. They want a boat that can maximize your miles and everything else. So, it’s got to perform well. Limited time requires a better-performing boat.”

The Promoter

Before he retired to the island of St. Maarten and found a second calling among a trio of islanders who created and run the annual Caribbean Multihull Challenge Race and Rally, Steve Burzon was a high-powered Manhattan advertising executive who, in his spare time, was a passionate sailor. Burzon was a member of the New York Yacht Club and occasionally participated in its summer race weeks, but at heart he was a cruiser, and the best times aboard his Swan 411, Albireo, were on trips to Maine or offshore forays to Bermuda and the sunny Caribe.

“The rally and the time trials really give everyone the opportunity to meet one another and have some fun. I think that’s why we’re seeing it growing. It’s about the sailing and the sailors.”

So, he certainly had the proper mindset to help run an event like the CMC, which celebrated its seventh running this past winter in support of the growing numbers of catamarans in the sailboat segment. The CMC, however, is evolving in an interesting and unexpected way. Two years ago, the organizers introduced a cruising rally to the festivities. Last year, the number of new rally entries surpassed those of the larger racing boats. One fun component of the rally venue, which takes the fleet from St. Maarten to Anguilla to St. Barts—basically a cruise in company—is the time trials. In fact, the top performer in the event’s recent running was a well-sailed Leopard 50 from Puerto Rico called La Novia, which has switched from the racing fleet to the rally one.

“It’s important to recognize that this is not a race. It’s for cruisers,” Burzon says. “A lot of cruisers don’t want to race because their insurance rates go up or they need to bring in crew. With the rally, there’s not a bunch of boats crashing a starting line to get a favorable spot. The time trials are a form of competition, but not against one another. It’s a race against time. You’re competing only against the clock.

“It’s a parade start,” he continues. “You get an assigned time to set off, and we take your time when you leave. We have handicap ratings for the boats, so it’s not just a matter of who is sailing the biggest boat. On the legs from St. Maarten to St. Barts and back, it’s basically a test of straight-line speed, on a power reach. But from St. Maarten to Marigot, you get a little bit of everything: upwind work, reaching, downwind sailing, all the points of sail. You have to succeed in all aspects. You’ve got to be good at everything. Those La Novia guys proved that. They’re really good sailors.”

The Caribbean Multihull Challenge has seen growing participation in its rally component. Georges Coutu’s well-sailed Leopard 50, La Novia, is one of many boats that has switched from the racing fleet to the rally group. Laurens Morel

And, at the end of the day, just like an actual race, there are bragging rights to be had. “When you’re cruising like I used to, you’re sort of by yourself,” he says. “You pull into a harbor, go for a swim, hang out with your family or your crew. You don’t normally hop in your dinghy and pop over to the boat next door. But the rally and the time trials really give everyone the opportunity to meet one another and have some fun. I think that’s why we’re seeing it growing. It’s about the sailing and the sailors.”

The Organizer

British sailor and author Jimmy Cornell pioneered the idea of grand ocean-crossing rallies back in the 1980s. In the intervening decades, the concept has exploded. The Salty Dawg Sailing Association runs its own full calendar of events; so do brands such as Oyster, with its continuing series of the Oyster World Rally, with one currently underway and another scheduled for 2028-29. But Cornell’s original World Cruising Club started it all and is still going strong, and its annual ARC Rally—the Atlantic Rally for Cruisers—remains its signature event.

These days, the club’s managing director is Paul Tetlow, who earned his sailing chops aboard a variety of boats and related expeditions during his years in the British military. As the organizer of the ARC, he acknowledges that competition plays a role in the proceedings, even among the die-hard cruisers.

“It’s a broad fleet with many varied interests, backgrounds and motivations,” he says. “Out of 150 boats and almost 1,000 people, we’re quite a broad church. Within that large group, there are lots of subsets, whether it’s the doublehanded crew, the family crew or the all-boys crew. We have racing divisions as well, so it’s a real different mix of motivations.

An added bonus of the rallies is the camaraderie at day’s end. Matthew Burzon

“That includes the offshore cruiser who is motivated by performing well and the fact that they’re among other boats and can mark their performance,” he adds, “either formally through a racing system or just by looking at the daily positions—which, informally, encourages them to sail well and get the most out of their boat’s performance.”

Of course, as the old saw goes, whenever any two boats are alongside, on whatever piece of water, they’re racing. I ask Tetlow: Once his fleet was underway, did the cruisers suddenly adopt a competitive streak?

“Yes,” he says with a laugh. “We warn people about that. We have a system and a process where we engage the boats to make sure we’ve got the data required to calculate a time-correction factor. If they’re at all interested in competition—and some don’t become interested until they’re actually crossing the Atlantic, and they develop a bit more of a competitive edge—we have the numbers to enter into it.

“I think having a competitive side to a cruising rally is probably a very healthy thing,” he adds. “It makes people really focus on getting the best performance out of their boat and crew without taking any unnecessary risks.”

At the close of each ARC, prizes are awarded to every category and division, racer and cruiser alike. And Tetlow’s closing thoughts can apply to any sailor, no matter the level of intensity, at the close of any passage: “We want to celebrate success. We want everyone to be safe and have fun.”

Thanks to our friends at CruisingWorld Magazine for this great article!

The Rules That Save Lives: Common Sense is a Sailor’s Best Safety Tool

It is every sailor’s responsibility to know the rules of the road and follow them, to prevent collisions and save lives.

By Gary Jobson

April 10, 2025

A diligent lookout and swift reactions can mean the difference between a close call and a disaster.

It’s foggy on a dark night. Our boat is sailing through a narrow channel at 10 knots. We hear a foghorn. Two minutes later, the horn sounds closer.

A few more horns are sounded. Out of the mist, a tugboat appears, crossing our bow at short range. As the vessel passes, I notice a hawser line extending from the stern into the water. I realize the tugboat is towing something.

Instantly, I turn the wheel and sail 180 degrees away from the tugboat. Our crew could hear the waves of an oncoming craft. We watched in horror as the faint outline of a barge slipped past.

Had I not maneuvered away, the barge would have rammed us. The sad episode took place more than 40 years ago, and I still have nightmares about what could have happened.

This near collision is a good example of why every boat should maintain a diligent lookout. In hindsight, we should have altered course earlier, when we first heard the foghorn. We also should have slowed down, communicated with the tugboat via radio, and taken careful bearings of the sound to understand the other vessel’s course.

Rules of the road are important and should be carefully followed. Common sense is the fundamental premise behind the rules that are designed to keep vessels from colliding.

In 1972, the International Maritime Organization wrote the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, or COLREGS. The basic rules for racing yachts are the Racing Rules of Sailing. Still, there are no traffic police on the water. Sailing is “self-regulated.” Major sailboat races often use umpires, either on the water or watching GPS tracks, to make rulings, but outside of tightly controlled races, most sailors are on their own.

Mariners on all vessels are expected to follow COLREGS. Anyone wanting to receive a license to operate a vessel needs to pass a comprehensive test with a 90 percent score. Competitive sailors spend years studying the Racing Rules of Sailing to find tactical advantages. Every four years, World Sailing, the international governing body of sailing, updates the rulebook to make racing more understandable.

But overall, the basic rules are relatively easy to grasp. There are only a handful of fundamental rules that govern what should happen when boats meet.

Crossing Situations

The vessel on starboard tack with the wind coming over the starboard side of the boat has the right-of-way. A port-tack yacht shall give way and stay clear. If two boats under power are heading on a collision course, then both vessels should alter course to starboard and pass on the port side of the boat.

If two boats under power are approaching each other at an angle, then the boat that has another vessel approaching from its starboard side shall keep clear and alter course to pass behind.

Overtaking

A faster boat passing a slower boat shall stay clear of the slower vessel.

Same Tack

When boats are sailing on the same tack, the windward boat (closest to the wind) is required to stay clear of a leeward boat.

Action by the Burdened (Give-Way) Boat

A burdened vessel that does not have the right-of-way shall take early and substantial action to stay clear. A major alteration of course helps the crew of the right-of-way boat recognize that action is being taken to avoid a collision.

Sailing in Confined Waters

Generally, a sailboat has the right-of-way over a powerboat. In restricted waters, a large vessel has the right-of-way over all vessels, including sailboats, because there is little room to maneuver.

I’ve been an officer on the bridge of naval and merchant vessels. It is frightening to see a small sailboat cross your bow and disappear. Sailors should never cross ahead of a large ship. Visibility is limited, and turning or slowing down takes a long time in a large vessel. If the crew of a large vessel believes that a problem is developing with a smaller vessel, they will sound five horn blasts.

Common sense dictates that small vessels must give large vessels room to pass safely. Vessels are required to navigate on the starboard side of a channel.

When Maneuvering

A boat that is tacking or jibing is obligated to stay clear of a boat that is sailing on a straight course.

Person in Charge

The skipper is the person in charge of a boat. The responsibility for sailing safely rests with the skipper.

Many years ago, as a cadet on a merchant training ship while steaming in the mid-Atlantic, I was sent to knock on the captain’s cabin door to alert him that we were on a close course with another vessel. I was nervous about waking him up at 0300. To my relief, he thanked me and went straight to the bridge, where he ordered a change of course.

Keep a Lookout

Good visibility is restricted on sailboats. For example, it is difficult to see to leeward through a headsail. At least one crewmember should always watch for boat traffic. This includes looking on the leeward side of the boat.

If another boat is approaching, it is the obligation of the lookout to inform the helmsperson and skipper about a potential collision. Clear communication is the key to safe passage.

Extreme Situations

If two boats appear to be heading for a collision, then both boats should take every possible action to avoid hitting. The US Coast Guard uses the term “immediate danger” when a close encounter becomes serious. Communications on a VHF radio are helpful when working to avoid a collision. In restricted waters with a lot of traffic, a VHF radio is an important asset. When two boats get close, hail your change in course and speed to the other boat.

Running Lights

The IMO requires vessels to carry lights at night, which is defined as the time between 30 minutes before sunset and 30 minutes after sunrise. Sailing vessels were first required to carry lights by an act of Congress in 1849.

The basic light package for sailing vessels is a green light on the starboard side, a red light on the port side, and a white line on the stern. Vessels smaller than 23 feet are required to carry at least a white light to signal their presence to other vessels at night.

Sailing in Shallow Water

Sailboats have a centerboard or keel to help with stability and the ability to sail a straight course. Sailboats must sail in deeper waters. It is important to stay particularly diligent when boats are navigating shallow waters and allow room for safe navigation.

Aircraft pilots are required to file a flight plan before taking off. Flight controllers monitor air-traffic control to keep people safe. There are no traffic controllers on the inland waters and high seas. Sailors are expected to be diligent on their own.

More: Gary Jobson, Hands-On Sailor, How To, safety at sea, seamanship

Little Harbor 60

Little Harbor Yachts is a renowned brand known for producing high-quality sailing yachts. Founded by Ted Hood in the 1950s, Little Harbor Yachts gained a reputation for building custom and semi-custom sailing yachts that were both luxurious and seaworthy. The company was based in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, and produced a range of yachts, including the Little Harbor 38, 42, 44, 46, 53, and 58 models, among others. These yachts were highly regarded for their craftsmanship, performance, and elegant design, making them popular among sailing enthusiasts and cruising aficionados.

The Little Harbor 60 is a classic sailing yacht known for its luxurious accommodations and excellent sailing performance. These yachts are highly regarded for their craftsmanship and seaworthiness. The 60-foot model offers spacious living areas, typically featuring a master stateroom, guest cabins, a salon, and a well-equipped galley. The yacht’s design allows for comfortable cruising and often includes amenities such as a cockpit for outdoor dining and relaxation.

REDSTART, a central listing with Wellington Yacht Partners, is a pristine Little Harbor 44 Yacht with exceptional performance and shoal draft. This Hood-designed sailing yacht offers a shallow 5’ draft (centerboard up), built to high standards with electric winches and furling mainsail for easy short-handed sailing. Featuring a sought-after two-stateroom/two-head layout, REDSTART provides both privacy and versatility. With only two owners and limited summertime use, she’s been meticulously maintained, including inside winter storage and recent upgrades—new hull and mast paint, sails, electronics, and more. Perfect for those seeking a high-quality, pedigree sailing yacht at a competitive price!”

LAMLASH ~ SOLD in 2023 is a highly customized Little Harbor 58/60 model with one foot added to the standard 58 hull for a longer aft deck, draft reduced by 8” to only 4’ – 6” with centerboard up, and mast height slightly lower (20”) to provide 75’ bridge clearance. She is also one of only two in the series that features a centerline queen berth aft. Like her sisterships, LAMLASH can be easily sailed by one thanks to a cockpit design that is second to none – all sail controls and winches are at the helm, and easy side exits to main deck. She also boasts finely crafted joinerwork above and below decks that is seldom if ever seen in newer yachts today. VIDEO ~ Little Harbor 59 ~ LAMLASH

It may seem like something out of science fiction: unmanned ocean-going ships. However, this futuristic vision is becoming a reality sooner than expected. In a Norwegian fjord, a large, lime-green vessel is undergoing testing, appearing much like any other ship at first glance. Yet, upon closer inspection, it reveals a suite of cutting-edge technology, including cameras, microphones, radars, GPS, and various satellite communication systems.

Read the entire article by Jonathan Amos, Rebecca Morelle and Alison Francis on BBC.com

https://bbc.com/news/science-environment-68486462

Photo credit: BBC/Kevin Church

Decommissioning a yacht for winter involves several important steps to protect the vessel from the harsh weather conditions and ensure that it remains in good condition during the off-season. Below is an article to guide you through the decommissioning process. By following this comprehensive checklist, you’ll help protect your yacht from the winter elements and ensure that it’s ready when the warmer weather returns. Keep in mind that specific requirements may vary based on the type of yacht, its construction, and the local climate, so consult your yacht’s manual and consider seeking professional advice if needed.

“Decommissioning Checklist” ~ By Charles Mason, SAIL Magazine

https://www.sailmagazine.com/diy/decommissioning-checklist

The Sat Comm Wars Are Heating Up – read this article in Cruising Compass about systems of satellites for sailors and the vendors who provide the hardware and software to access the system.

Little Harbor 44

New owner shares his journey to prepare living aboard his Little Harbor 44 in the Chesapeake Bay area.

https://forums.sailinganarchy.com/threads/life-aboard-a-little-harbor-44.240117/

Reprinted with permission from the “On the Wind” column by Chris Caswell. Originally published in SAILING Magazine, copyright March, 2012.

Author Chris Caswell

Coincidence is a funny thing sometimes. I had been musing recently about sailing, which isn’t particularly unusual because I spend way too much of my time thinking about sailing, daydreaming about sailing, and wishing I was sailing. And, of course, I spend a lot of time sailing, too.

But I’d been trying to find a single thread that would explain why I love sailing and it seemed quite impossible because sailing has so many facets. There is daysailing and cruising and racing and just tinkering on your boat. It’s all about wind and sun and water, but I thought there had to be something in common that makes sailing so appealing. Trying to distill that one essence was eluding me.

And then I came across a piece in the New York Times that was discussing the future of marketing to the younger generation and the consensus was one word: stillness.

The point of the article was that, less than a generation after we developed all these devices—from the Internet to cell phones to computers—that would supposedly simplify our lives and give us more free time, we were trying to escape them. They were consuming our lives, and devouring our free time. And that is what the marketing gurus forecast as the trend of the future: getting away.

The light bulb that went on above my head must have been a blinding flash clearly visible for miles. Sailing is about getting away, and that is what I love so much. It doesn’t matter whether you are drifting along aimlessly or thrashing around the buoys, sailing is getting away.

There was a time recently when a fad among hotels was the “Blackberry Detox Weekend,” where guests would stay in an upscale room and actually pay for the requirement to leave their Blackberry or cell phone at the front desk, thus disconnecting themselves for a few days to decompress from our rush-rush life.

The New York Times article pointed out that guests pay more than $2,200 a night to stay at the Post Ranch Inn on California’s Big Sur coast, where one of the selling points is not having a television in the room. There are Internet “rescue camps” springing up to help wean kids off their addiction to video screens of all sizes.

In the Pulitizer-nominated book The Shallows, which is subtitled “What the Internet is doing to our brains,” author Nicholas Carr argues that the Internet has a deleterious effect on both our concentration and our contemplation.

The average American spends more than eight hours in front of a screen, either computer or television, and the hours spent on line literally doubled between 2005 and 2009. According to a Nielsen survey, teenagers send or receive more than 3,300 text messages every month. That works out to more than four messages an hour, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Yipes!

All this massive input of information, coming at us from the computer, from television, from cell phones that ring constantly, has deprived us of the time to actually relax and, to use a word not often heard, to contemplate. And that is exactly the pleasure of sailing.

The New York Times author labeled it “stillness” but sailing, even in a flat calm, isn’t about stillness. There is the sound of the bow wave, perhaps the tap of a line or halyard in the breeze, the rustle of the sails. But sailing allows us to disconnect, to unplug, to actually savor our lives.

The New York Times article cited studies that show how, after test subjects spent time in quiet rural settings, they showed “greater attentiveness, stronger memory, and generally improved cognition.” Their brains became both calmer and sharper.

I know this from personal experience because during my college days I had to make a choice between studying for a final exam in a class in which I wasn’t doing well and sailing in the Snipe Nationals. The Snipe Nationals won, of course, and I didn’t crack a book over the entire weekend. But on Monday morning, I aced the exam with my highest score that semester. The defense rests.

It’s also been pointed out that our world has become increasing uncivil. Road rage is on the uptick, saying thank you has gone out of style, and even holding a door open for another person is a lost gesture. Neuroscientists note that empathy (and, therefore, courtesy) is a function of relaxed neural processes. And there is no time in our oh-so-busy modern society for any relaxation.

Except when you are sailing.

Will sailing cure all of societies ills? Probably not. But sailing is a time when you can take a mental deep breath and let your mind drift, free of interruptions. You can actually have a conversation with your spouse and your family. Even when you are racing, sailing has a calming effect because you are totally focused and there are none of the moment-to-moment irritations of incoming emails or ringing phones.

The marketing gurus may want to sell us getaway weekends, but sailors know they already have that luxury. Just the ability to cast off all your links to the world as easily as you cast off your dock lines is, in itself, a gift.